We’ve all heard of deep learning and deep neural networks, but what exactly does it mean?

In this post, we’ll learn about deep learning and what a deep CNN architecture looks like.

We might have to start with the most familiar term Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs). ANNs are computing systems inspired by the model of the human brain and is designed to simulate the way the human brain processes and analyzes information. Like the human brain, ANNs are built with interconnected units or nodes called neurons, which transmit signals to each other. Typically, neurons are collected into layers, where different layers could perform different operations on their inputs. A deep network refers to how much layers are there in the neural net.

Here’s an interesting quote from Jeff Dean [1]:

“When you hear the term deep learning, just think of a large, deep neural net. Deep refers to the number of layers typically and so this kind of popular term that’s been adopted in the press.”

Okay, so how deep is deep?

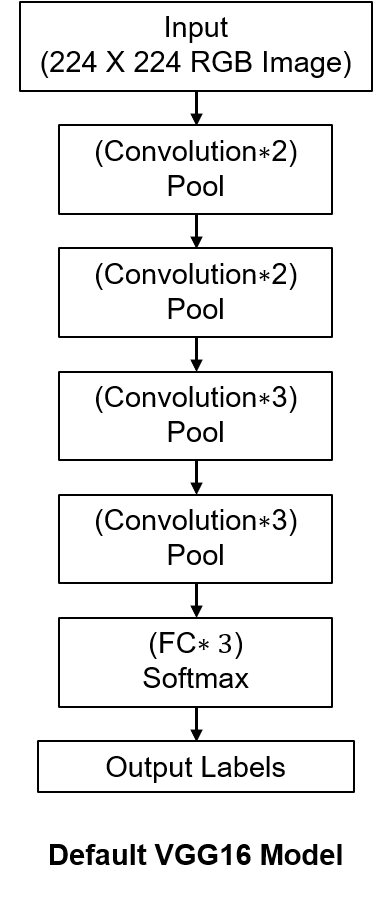

Deep CNNs will be employed here, because they are known to learn more efficiently than shallow CNNs by naturally integrating incredibly enrichened image features[19]. A representative robust and easily-trainable deep CNN architecture, VGG16, is selected for this example[20].

Here is a brief overview of the VGG16 architecture:

VGG16 is a convolutional neural network model proposed by K. Simonyan and A. Zisserman from the University of Oxford in the paper “Very Deep Convolutional Networks for Large-Scale Image Recognition”. The model achieves 92.7% top-5 test accuracy in ImageNet, which is a dataset of over 14 million images belonging to 1000 classes. It was one of the famous model submitted to ILSVRC-2014. It makes the improvement over AlexNet by replacing large kernel-sized filters (11 and 5 in the first and second convolutional layer, respectively) with multiple 3×3 kernel-sized filters one after another. VGG16 was trained for weeks and was using NVIDIA Titan Black GPU’s.

The input to cov1 layer is of fixed size 224 x 224 RGB image. The image is passed through a stack of convolutional (conv.) layers, where the filters were used with a very small receptive field: 3×3 (which is the smallest size to capture the notion of left/right, up/down, center). In one of the configurations, it also utilizes 1×1 convolution filters, which can be seen as a linear transformation of the input channels (followed by non-linearity). The convolution stride is fixed to 1 pixel; the spatial padding of conv. layer input is such that the spatial resolution is preserved after convolution, i.e. the padding is 1-pixel for 3×3 conv. layers. Spatial pooling is carried out by five max-pooling layers, which follow some of the conv. layers (not all the conv. layers are followed by max-pooling). Max-pooling is performed over a 2×2 pixel window, with stride 2.

Three Fully-Connected (FC) layers follow a stack of convolutional layers (which has a different depth in different architectures): the first two have 4096 channels each, the third performs 1000-way ILSVRC classification and thus contains 1000 channels (one for each class). The final layer is the soft-max layer. The configuration of the fully connected layers is the same in all networks.

All hidden layers are equipped with the rectification (ReLU) non-linearity. It is also noted that none of the networks (except for one) contain Local Response Normalisation (LRN), such normalization does not improve the performance on the ILSVRC dataset, but leads to increased memory consumption and computation time. Original Vgg16 description from neurohive.io

References

- Jeff Dean. Results Get Better With More Data, Larger Models, More Compute. http://static.googleusercontent.com/media/research.google.com/en//people/jeff/BayLearn2015.pdf. 2016 (cited on page 27).